Saint Martin and the Eleventh Hour: The Overlapping Meanings of November 11

By Benjamin Fishbein

On November 11, 1918, the armistice that ended the First World War was signed in Compiègne, France. Today, many of the nations that fought in the war celebrate that armistice and veterans in general. The holiday goes by many names: Veteran’s Day in the United States, Remembrance Day in the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth, and Armistice Day in France and Belgium. However, November 11 is also commemorated for another reason: the feast day of St. Martin of Tours. One of the Catholic Church’s most important saints, St. Martin served as a soldier in the Roman Army and lived in what is now France. Is this just a coincidence, or is there a relationship between this French military saint and the ending of one of the bloodiest wars in French history?

An Orthodox Icon of St. Martin

St. Martin was born in what is now Hungary, sometime in the early fourth century. He came to Gaul as a soldier and ended up as the Bishop of Caesarodunum, the city which is now Tours, France. According to the earliest hagiographic account of Martin’s life, Sulpicius Severus’ Vita Martini, Martin converted to Christianity at the age of ten, against his parents’ will, and his subsequent military service was forced upon him by an imperial edict (Burton 2017, 97). This may be true, but it is also clear that Severus’ goal is to present Martin as an ideal saintly figure, and many details of his life may be exaggerated. It is just as possible he was happy to join the army, and in later periods Martin’s association with the military would be celebrated. The earliest medieval cult of Martin, however, tended to downplay the image of Martin the Soldier in favor of Martin the peaceful Bishop. Gregory of Tours, who was the bishop of Martin’s diocese in the sixth century, and who wrote an extensive collection of Martin’s miracles, even recorded a miracle story in which a dream appearance of the saint dressed as a soldier is revealed to be the work of a demon (Van Dam 1993, 237).

Martin died on November 8, 397. In his Histories, Gregory of Tours describes a conflict between the citizens of Poitiers and Tours over who should get to keep the saint’s body, with the people of Tours eventually stealing the saint’s body while the Poitevins were sleeping (Thorpe 1974, 98-99). This fight caused a delay in burial, but Martin was finally interred in Tours on November 11, and this became his feast day, also known as Martinmas. It became an important date on the agricultural calendar: Martinmas was the traditional date for the slaughtering of livestock in preparation for the winter (Homans 1975, 379). In fact, Martinmas used to mark the beginning of the season of Advent, which was called “St. Martin’s Lent” (Talley 1986, 151). Advent was eventually shortened, and now only comprises the four weeks before Christmas.

In the 19th century, the French Third Republic revived the cult of St. Martin and promoted the image of Martin as a soldier-saint, a symbol of French nationalism, and the growing alliance between right wing political forces and the Church. During the Franco-Prussian War, Saint Martin was called upon to protect France, and at Tours a weekly "military mass” was held at Martin’s tomb for soldiers and their families. Martin was even promoted as a masculine replacement of Marianne, the female personification of France famous from Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People (Brennan 1997, 491-492). As defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the establishment of the Paris Commune in 1871, reactionary elements in the Army and the Government embraced Catholicism, and with it Martin, as a counter to growing class conflict (Brennan 1997, 492-493). When the First World War began in 1914, Martin continued to be used as a French military symbol, alongside military saints from other allied nations such as Britain’s St. George (Brennan 1997, 492).

The current Basilica of St. Martin in Tours was built between 1886 and 1924

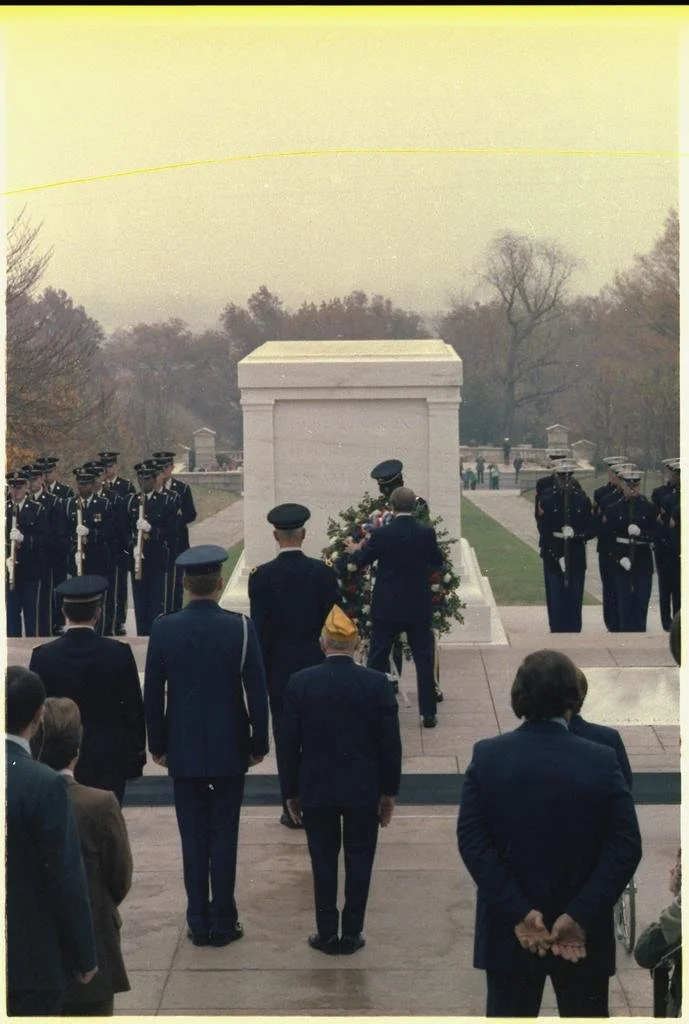

To answer the question posed in this blog posts’ introduction, there is no explicit evidence that the choice of November 11th for the signing of the World War 1 armistice had anything to do with it also being the Feast of Saint Martin. However, when the war finally came to an end, at the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month,” French Catholics were quick to attribute the victory to Martin. Immense celebrations were held in Paris, at Notre-Dame and Sacre-Coeur, as well as at Martin’s shrine in Tours. A few days later, on November 17, a large military mass was held at Tours which included soldiers from all the allied nations, high-ranking clergy, and French politicians. The flags of France, the United States, and other allied nations were placed before Martin’s tomb alongside laurel wreaths (Brennan 1997, 500-501).

These descriptions sound very similar to the types of secular Armistice Day celebrations that occur today. Ceremonies are often held at symbolic “Tombs of the Unknown Soldier” and include the placement of flags and wreaths. Even if the association is just a coincidence, the Catholic Church continues to blend together celebrations of Saint Martin’s Day with celebrations of the Armistice. On the hundredth anniversary of the armistice in 2018, at St. Martin’s shrine in Tours, both “armistice masses” and masses for St. Martin’s feast were celebrated, which included the placement of French and American flags in the church, just as in 1918. Though seemingly a coincidence, the convergence of St. Martin’s Day and Armistice celebrations highlights how civic society and religious practice can intersect. Not only is there a, perhaps expected, sacralization of a secular memorial, but also the introduction of that civic commemoration into the realm of religious ritual.

President Jimmy Carter lays a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Solider, in Arlington National Cemetery, for Veteran’s Day.

Works Cited

Brennan, Brian. “The Revival of the Cult of Martin of Tours in the Third Republic.” Church History 66, no. 3 (1997): 489-501.

Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. Penguin Books, 1974.

Gregory of Tours. “The Miracles of the Bishop St. Martin.” In Saints and Their Miracles in Late Antique Gaul. Edited and Translated by Raymond Van Dam. Princeton University Press, 1993.

Homans, George Caspar. English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century. W. W. Norton, 1975.

Severus, Sulpicius. Vita Martini. Edited and Translated by Philip Burton. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Talley, Thomas J. The Origins of the Liturgical Year. Pueblo Publishing Company, 1986.