How Historically Accurate is Derry Girls?

By Alexandra Smithie

Sally Rooney’s “Normal People” took over bookshelves, Cillian Murphy won “Best Actor” in 2024, and Paul Mescal has become one of TV’s biggest heartthrobs. Riding on this “Green Wave” of Irish pop culture, it’s no surprise that Lisa McGee’s period teen sitcom Derry Girls has become immensely popular in the United States. But just how historically accurate is Derry Girls? To the Northern Irish public who lived through this time period, the answer is “very.”

Left to right: Orla McCool (Louisa Harland), Claire Devlin (Nicola Coughlan), Erin Quinn (Saoirse-Monica Jackson), James Maguire (Dylan Llewellyn), Michelle Mallon (Jamie-Lee O’Donnell). (IMDB)

Derry Girls is not just a charming coming-of-age comedy. Although the plot itself is fictional, it is set in 1990s Derry (or Londonderry, “according to your persuasion”) during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The show focuses on four Irish Catholic girls: Erin Quinn, Orla McCool, Claire Devlin, and Michelle Mallon, and Michelle’s English cousin James Maguire, who attend an all-girls convent school. Although the show is very funny, it takes place against the disturbing backdrop of horrific sectarian violence and seemingly unsolvable political strife that characterized Northern Irish life for decades. Derry Girls is rooted in history, relying on major events to book-end the seasons, as well as to set up absurd situations for the characters.

A bomb technician on his way to defuse a bomb, next to a sign that reads “Prepare to meet thy God.” The conflict played out on the ground and in daily life, producing striking images like this one. (Wikimedia Commons)

The girls and their families are accustomed to soldiers and bomb threats, which are daily inconveniences to them. Orla’s mom and Erin’s aunt Sarah McCool says that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) plants bombs in order to inconvenience normal people, because a bridge closure means she can’t get to her tanning appointment. When their great-uncle Colm is tied to his radiator by the IRA so they can “borrow” his van, Sarah is excited to talk about it on TV so that she can get free fries from the fish-and-chips shop.

In contrast, James, the English outsider, is shocked and horrified by the conflict and the ways it infiltrates their lives. James is the first male student to attend Our Lady Immaculate College, the all-girls Catholic convent school that the girls attend. His Englishness prevents him from attending an all-boys Catholic school, while his Catholicism prevents him from attending an all-boys Protestant school. Although this is a funny situation, it reflects the real fear that James would be subjected to religious or political violence at school just because of his background.

Erin and Orla’s family dynamics also reflect the culture of the period. Their grandfather Joe McCool is harsh to his son-in-law, Gerry Quinn, who is from the Republic of Ireland, also known as the Free State (Joe calls him a “Free State F–cker”). These tensions come out when the family is escaping to the Free State during the July Orange Order Parades. Every July 12th, the Protestant Orange Order holds hundreds of parades throughout Northern Ireland to commemorate the 1690 Battle of the Boyne, where the Protestant William of Orange defeated the Catholic King James II. During the Troubles, the Orange parades were often an opportunity for Protestant groups to harass and intimidate Catholic civilians. These parades still occur every year, with vigorous debate sparking every time. Protestants see them as a form of cultural expression, while Catholics see the parades as a commemoration of past violence.

The Orangemen march every year on July 12th. This photo was taken in 2016 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, which now has a Catholic majority. (Wikimedia Commons)

While the Quinn/McCool family is escaping, they find IRA member “Emmett” in their trunk, trying to cross the border into the Free State undetected. Joe, who presumably grew up in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising, is much more sympathetic to the IRA man and tells Gerry that he’s spineless for not wanting to smuggle him over the border. When Gerry asks “Emmett” if he’s killed anybody, “Emmett” responds with “not directly.” When “Emmett” asks Gerry if he recognizes the legal system of a brutal colonial oppressor (the United Kingdom), Gerry responds that if that system can put him in jail for twenty years, he recognizes it. This reflects how different generations saw the conflict. Joe’s sympathy for the IRA comes from nostalgia and sentimentality about the Republican cause, while Gerry’s fear of being caught up in smuggling a terrorist is a practical concern for his safety and that of his family.

The Provisional IRA split off from the Official IRA in 1969 due to a disagreement about how to resist British rule. The Provisional IRA embraced the armed struggle. Their favorite weapon was the AR-15, or Armalite, pictured here, and Volunteers wore balaclavas to conceal their identities. (Wikimedia Commons)

Gerry and Joe’s squabbles may be reflective of stereotypical father-in-law/son-in-law dynamics, but, more meaningfully, they show how generational and geographic differences led to different attitudes towards the conflict. Although this situation might seem absurd to American viewers (we instinctively take Gerry’s side), many Northern Irish families have had to deal with inter-generational conflict about attitudes towards the Troubles. Harboring or smuggling a friend or family member who was a paramilitary member, even if it was illegal, was a feature of daily life (as well as a source of internal conflict) for many Northern Irish families.

Lisa McGee deals with complex themes like intergenerational trauma, the taboo of homosexuality in the Catholic world, and the impact of violence on average people without sentimentalizing the conflict or taking an explicit side. While the show is told from a Catholic perspective based on McGee’s childhood, it presents the girls’ Protestant peers as equally innocent, growing up in the same violent and fraught society that makes them misunderstand and fear each other. The average person in Northern Ireland was not a paramilitary member, and feared violence by all terrorist groups, something that is easy to lose sight of because the conflict was sectarian in nature.

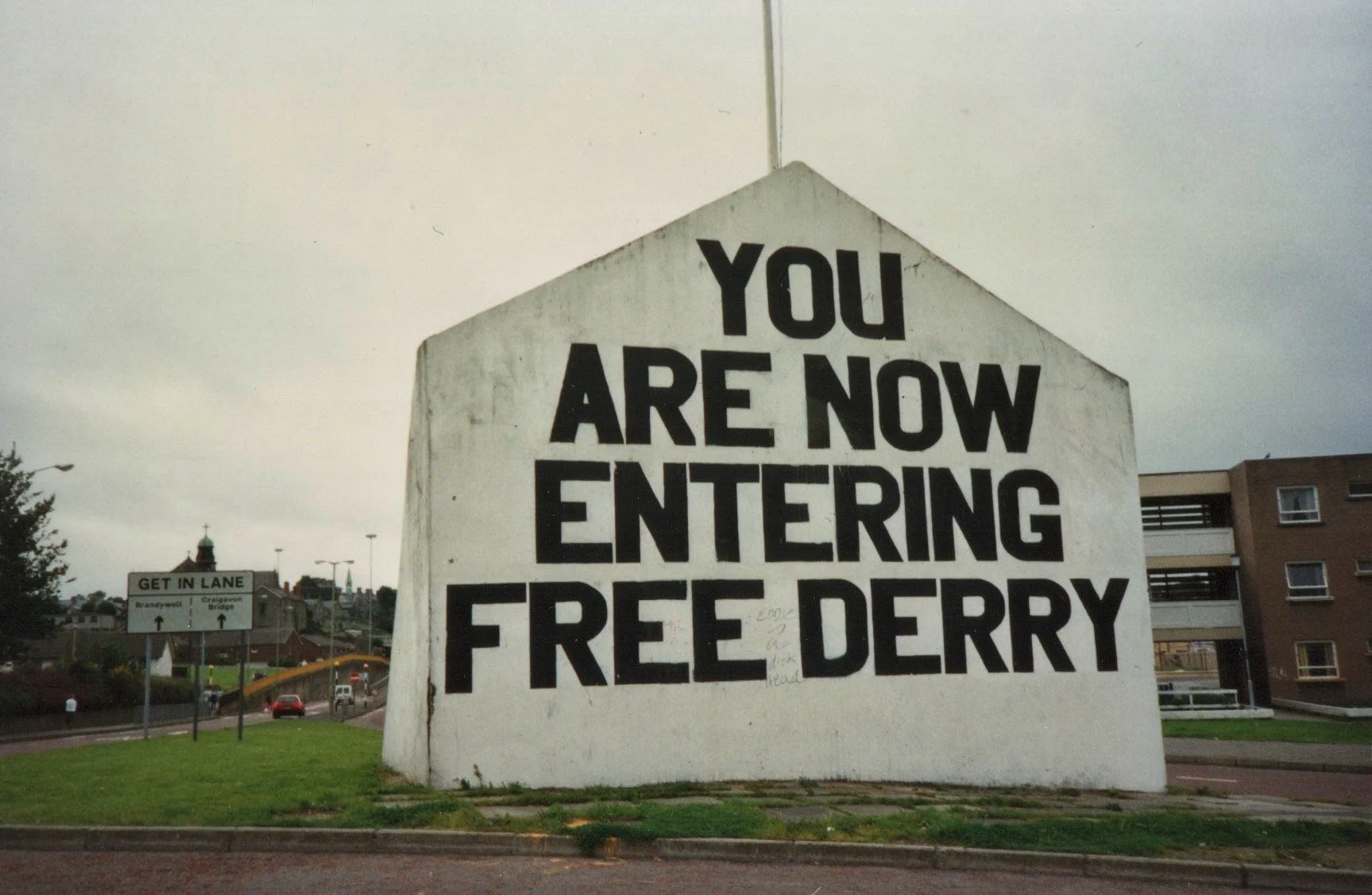

In the aftermath of the Bogside protests, “Free Derry” was established as a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist zone from 1969-1972, during the Civil Rights movement. This mural, which is still there today, is featured in Derry Girls. (Wiki Commons)

Much of the media about Northern Ireland’s Troubles risks romanticizing the conflict and doing injustice to the real people who lived through that time. The strength of Derry Girls lies in its attention to detail and respect for history. It reflects a new trend in history to tell stories from the perspective of those who were previously ignored. In the past, these types of stories would be dismissed, as the teenage coming-of-age perspective was not seen as important to understanding history. Although fictional, Derry Girls does justice to the Northern Irish public because it makes their daily lives and personal issues important, putting them in the context of the Troubles but not entirely defining Northern Irish people by their religion or political persuasion.

Erin and her friends participated in a “Friends Across The Barricade" program. These retreats allowed Catholic and Protestant youths from opposite sides of the conflict to meet each other and form friendships. Due to the sectarian nature of the conflict, Catholics and Protestants are still highly segregated in terms of housing, schools, and even physically with “peace walls” and other barriers. (IMDB)

Arguably, the strongest aspect of Derry Girls is its thoughtful and intentional engagement with history. McGee weaves together the characters’ personal lives and issues with the larger conflict without fetishizing violence or terrorism. Her incredible attention to detail makes the show very authentic; while the characters are fictional, they navigate the real world and respond to events that had a big impact on Northern Irish people who are still alive today. Her use of slang, 90s pop culture and music (the theme song is “Dreams” by the Cranberries), and changing attitudes from pessimism to optimism as the peace accords come closer reflect a deep engagement with the time period. McGee’s careful consideration of intricate social structures, institutions, culture, and history makes Derry Girls unique among period shows, honoring people that were previously dismissed and giving Northern Irish people at least part of the justice they deserve.

The Derry Girls mural in Derry. Love for the show has united people from Derry/Londonderry. (Geograph UK)